Doubt: The Invisible Conversation

Karl Giberson

Faith and doubt need to go together and the former needs to stop fearing the latter. And by doubt I mean real actual doubt: Did Jesus really rise from the dead? Does the truth of evolution mean that God did not create the world? Does God even exist? Are those rich TV preachers total frauds? The only kind of doubt I have ever seen welcomed—tolerated might be a better word—in my Christian experience is of the trivial kind: Can I believe in God’s leading when the paths seem blocked? Can I trust God to get me a girlfriend?

Evangelicals seem to view doubt like a cancer. Announce that you have doubts about the existence of God and the response will be the same as if you announced that you have a brain tumor: “That is terrible. I will pray for you.”

My personal history in Christian higher education has driven home this point for me. And recent polls about young people leaving their churches are confirming this. Evangelical colleges insist that their faculty—and often their students—live in a tension that breeds dishonesty. On the one hand, faculty sign documents affirming the mission statement of their employer; and on the other hand, faculty are encouraged to engage in intellectual explorations that might lead them to question that mission statement.

These explorations are not trivial. I have personally known evangelical faculty whose research led them into dangerous precincts. The following are representative of actual challenges with which my colleagues have wrestled—names withheld for obvious reasons! I have known New Testament scholars who concluded that the virgin birth stories are not reliable. (After all, the Old Testament prophecy is misquoted.) Or that Jesus could not have had the famous conversation with Nicodemus in John 3. (Turns out that conversation has some clever Greek wordplay and Jesus did not know Greek.) I know theologians who don’t consider the physical resurrection of Jesus important. One scholar, in a quiet conversation among friends, suggested that his audience “Draw the trajectory of Jesus ascension.” If you try this exercise you will begin to understand the problem.

In my own investigations, I became convinced that evolution was true; this led me to doubt that Adam and Eve were historical characters. In my earlier books I offered various ways to salvage some historicity for the first couple and their infamous fall, but in my new book--Saving the Original Sinner—I state without hesitation that Adam and Eve are simply not real. When it comes to Adam & Eve my investigations took me from belief, to doubt, to disbelief. Is this OK?

Various evangelical leaders were quite insistent that it was not OK. They attacked me personally for my views and criticized ENC and then Gordon College for employing me. They rejoiced when ENC announced I was leaving.

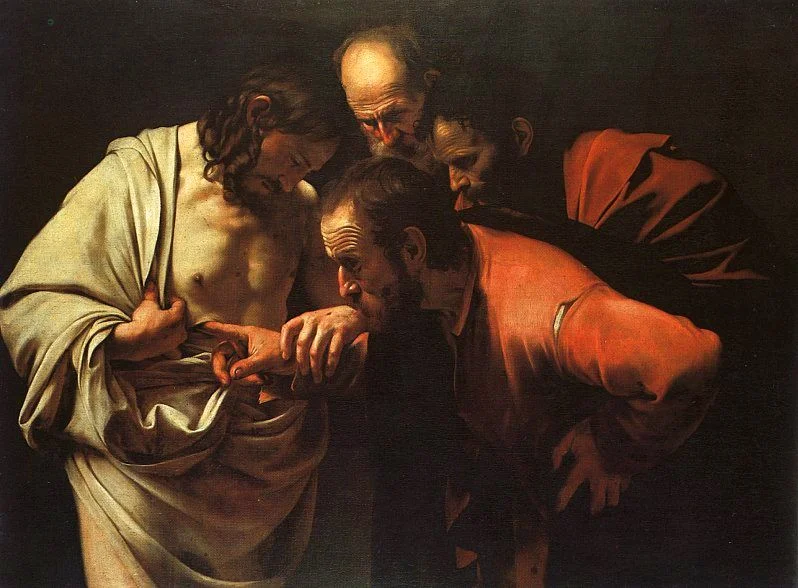

What are scholars to do about this state of affairs? In an ideal world with jobs available everywhere we could suppose that scholars might simply leave one college and go to another when they find themselves “outside” the mission statement. But we don’t live in an ideal world. In most cases the doubting Professor Thomases work hard to convince themselves that they don’t really disbelieve in this or that doctrine. When this fails, they work hard to prevent anyone from finding out that they disbelieve.

This process lacks integrity on several levels: In the first place, institutions need to be examining their mission statements. If those mission statements insist the earth is 10,000 years old and the geologists claim this cannot be true, then the mission statement is the problem, not the geologists. Wheaton College right now insists that Adam and Eve are not evolved creatures, like all other life on this planet. Wheaton’s mission statement is simply wrong on this point and no faculty member should be run off for pointing this out. In the second place, faculty members should not be placed in situations where they need to hide their doubts, either from themselves or their employers.

I left the Church of the Nazarene in 2010 after almost three decades of faithful service at Eastern Nazarene College. I felt beaten up and pessimistic about evangelicalism and needed to put it behind me. I had spent years defending science against attacks from people who knew nothing about science, beyond the challenges it posed to a literal reading of the Bible. I was constantly subjected to negative attacks from fundamentalists, most of them deeply influenced by biblical literalists like Ken Ham. Pastors would write me letters demanding I explain my views and insisting that I was leading students astray by planting seeds of doubt in their mind. In reality I was allowing my students to think, even when such thinking raised questions in their minds about what they believed.

I now work at Stonehill College, a Catholic liberal arts institution, where I teach Science & Religion. My experience there has been eye-opening and I now understand why Catholic colleges are so much stronger academically—think Notre Dame, Georgetown, Boston College, Holy Cross—than their evangelical counterparts: Catholic institutions do not appear to be afraid of threatening ideas. Honest doubters are welcome in the conversation, as conversation partners. Most Catholic schools demonstrate a confidence in their tradition that it does not need to be protected from the challenges posed by those who doubt, whether those doubters are protestants, members of non-Christian religions, atheists, or even disenchanted former Catholics.

My students at Stonehill—mostly Catholic—are much like my former students at Eastern Nazarene and Gordon Colleges—mostly evangelical. Both groups of students are thoughtful young people on spiritual journeys. But the evangelical students are, in most cases, receiving a pre-packaged set of ideas, with “right answers” already specified on topics like gay marriage, Adam & Eve, the truth of Christianity, the existence of God and so on. Doubt is neither encouraged nor welcomed. And, if Barna’s surveys are to be trusted, these young people are rejecting prepackaged belief systems. Young people need the freedom to doubt, to travel their own journey and arrive with integrity at their own destination, not the one prepared for them by their parents, pastors, and college administration.

Students whose spiritual journeys take them outside the boundaries of their youth too often feel they have no choice but to leave their faith traditions; after all, doubters are not welcome. The conversation needs to be much broader, with room for students to wander in and out of faith, without having to explicitly reject the faith of their childhood until they know where they have arrived.

Originally posted in God and Nature Magazine in summer 2015.